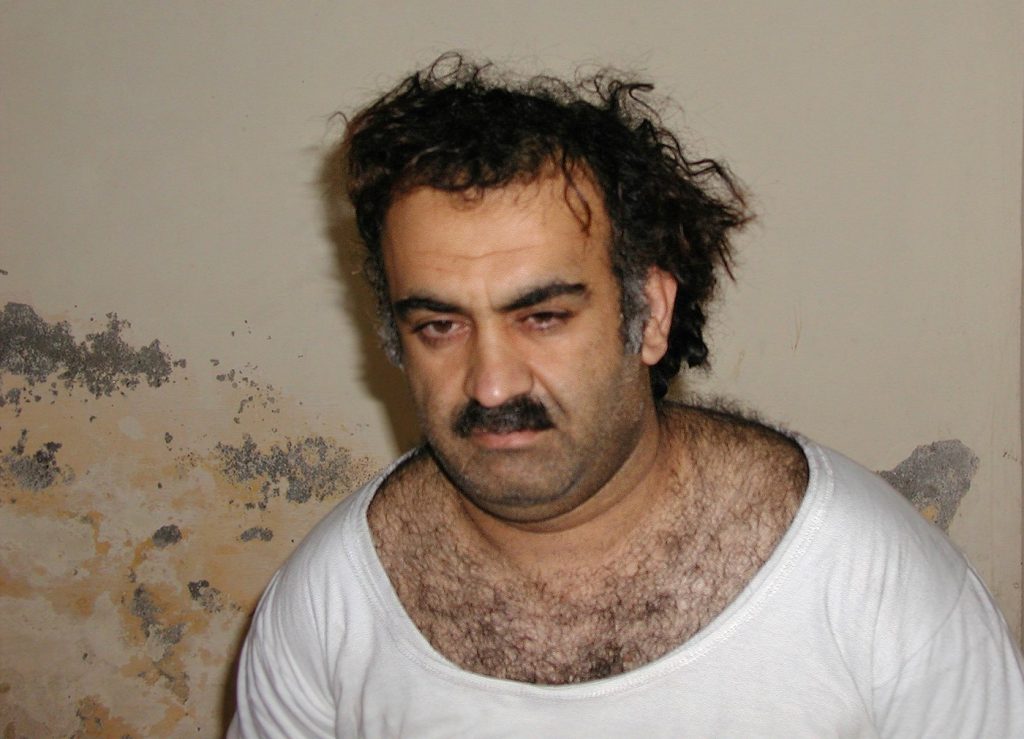

A divided federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., has thrown out an agreement that would have allowed Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind behind the September 11 attacks, to plead guilty in a deal that spared him the risk of execution. This ruling, delivered on Friday, effectively undoes efforts aimed at resolving a military prosecution that has faced numerous legal and logistical challenges for over two decades.

The plea deal, which took two years to negotiate and was approved by military prosecutors as well as the Pentagon's top official for Guantanamo Bay, stipulated life sentences without parole for Mohammed and two co-defendants. These men are accused of coordinating the 2001 al-Qaida attacks that resulted in significant loss of life, including the tragic crashes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, with another plane ending in a Pennsylvania field.

Families of the September 11 victims expressed mixed feelings regarding the plea agreement. Some family members believed that a trial would be a more appropriate avenue for justice and would provide critical information about the attacks, while others viewed the plea deal as the best hope for resolving the case and obtaining answers from the defendants. The plea agreement would have required the men to respond to lingering questions from the victims' families regarding the attacks.

However, then-Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin rejected the deal, arguing that decisions regarding the death penalty in a case as grave as September 11 should rest solely with the Secretary of Defense. Attorneys for the defendants contended that the agreement was already legally binding and that Austin acted too late to nullify it. Initially, a military judge and a military appeals panel sided with the defense arguments.

Ultimately, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled by a 2-1 vote that Austin had acted within his jurisdiction and criticized the military judge’s earlier ruling. Judges Patricia Millett and Neomi Rao noted that the Secretary, having assumed the convening authority, ensured that military commission trials were conducted, emphasizing that families and the American public deserved this opportunity.

In a dissenting opinion, Judge Robert Wilkins claimed that the government failed to prove that the military judge made an error. Responses from family members were similarly varied. Brett Eagleson, who was only 15 when his father was killed, regarded the appellate ruling as a “good win, for now.” He expressed concerns that a plea deal would allow the case to be quietly set aside without full accountability. Eagleson criticized the deal’s provision for the defendants to answer families' questions, doubting their sincerity.

On the other hand, Elizabeth Miller, who was six when her father, firefighter Douglas Miller, died in the attacks, supported the deal. She acknowledged the desire for a trial but emphasized the ongoing delays that have persisted into 2025, expressing skepticism about the feasibility of a trial at this stage. Miller’s opposition to the death penalty informed her belief that the plea deal was a practical solution given the circumstances.

As this legal battle continues without immediate resolution, the decisions made by the courts and opinions from the victims’ families highlight the complex dynamics surrounding justice and accountability in the aftermath of one of America’s most devastating terrorist attacks. The ruling marks yet another chapter in the long-standing efforts to bring Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his co-defendants to justice.