For the last two months of their lives in the United States, José Alberto González and his family spent nearly all their time isolated in their one-bedroom apartment in Denver, Colorado. They communicated only with their roommates, another Venezuelan family, and relied on WhatsApp messages to receive warnings about immigration agents in the area. Much of their daily routine revolved around their children's education, as González's wife took their 6- and 3-year-olds to school at 7:20 a.m. each morning.

The motivation for their journey to the U.S. two years ago stemmed from the hope of their children learning English in American schools and the necessity of finding work. They originally intended to stay in the U.S. for a decade. However, circumstances changed rapidly, and by February 28, González and his family were boarding a bus from Denver to El Paso with the intention of returning to Venezuela.

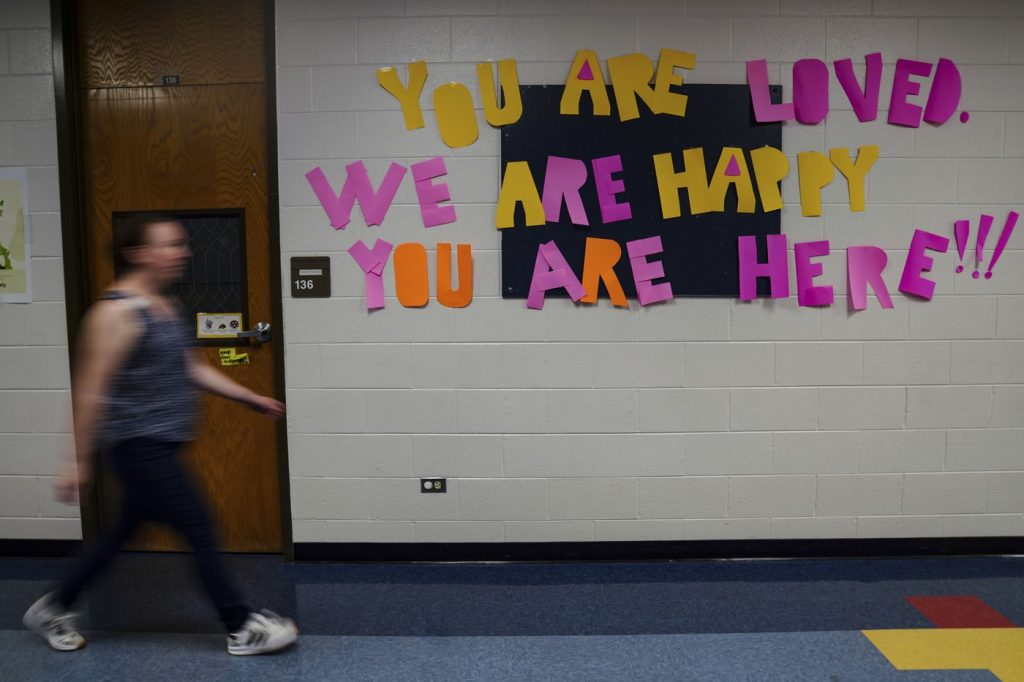

Despite growing fears among immigrant families about encounters with immigration authorities, many are still sending their children to school. Nevertheless, families are increasingly notifying schools of their intent to leave the country. The Department of Homeland Security reports that numerous immigrants are opting for "self-deportation". This decision is reportedly influenced by President Donald Trump's administration, which has fostered fears among immigrant communities through heightened surveillance and offers of financial incentives for families to leave.

On February 28, the Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to revoke legal protections from thousands of Venezuelan immigrants, raising concerns about deportation among many families. The principal of a Denver elementary school noted the high levels of fear and uncertainty guiding parents' decisions in this climate.

González realized it was time to leave when Trump was elected, and he was ready to return to Venezuela, even if it meant accepting a significantly lower income. He expressed his unwillingness to be viewed as a criminal due to his Venezuelan heritage and tattoos. It took him months to save enough money to bring his family home, which included traveling overland.

In late February, his apprehension escalated as rumors circulated about immigration raids targeting schools. Consequently, González kept his son at home and eventually withdrew both children from school, informing school administrators of their plans to return to Venezuela.

The pattern of dropping school attendance among immigrant families correlated with concerns over possible immigration enforcement. Denver Public Schools noted a 3% decline in attendance in February compared to the previous year, with even steeper declines at schools serving a significant number of immigrant students. Similar attendance drops were reported in various states following the election, reflecting widespread fear within immigrant communities.

Across the U.S., countries with large immigrant populations are noticing increased applications for passports amidst these circumstances. Data from the Brazilian Foreign Ministry indicated a 36% increase in passport applications in March, while Guatemalan authorities reported a 5% rise. Many immigrant families, like Melvin Josué from Honduras, are taking proactive steps to secure necessary travel documents for their families as they contemplate returning home.

As such worries about detention and employment challenges loom larger, immigrants are grappling with whether life in the U.S. remains viable. Trump’s offer to pay for transportation and offer monetary assistance as incentives for families considering departure has added urgency to these decisions.

Now back in Venezuela, González advises other immigrants in the U.S. to return independently, as he no longer trusts the U.S. government. He encourages those inquiring about returning to prepare financially and suggests that it is easier to make the journey south than it was to reach the U.S. initially.