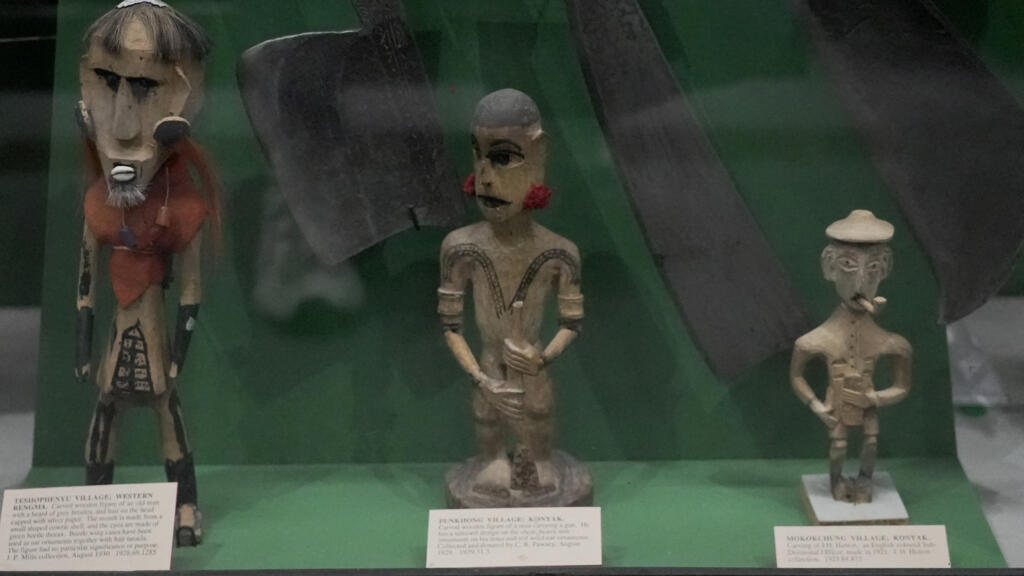

In a significant discourse surrounding cultural heritage and reparative justice, tribes from Nagaland, located in northeastern India, have engaged in discussions at the esteemed Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University. The focal point of these talks is the repatriation of ancestral remains that were taken during the colonial era. For decades, these remains, often classified as "trophies," including skulls and various body parts, have been exhibited to the public at this prominent institution.

The Pitt Rivers Museum, known for its extensive collection of anthropological artifacts, has been a site of contention as tribes advocate for the return of their cultural and human heritage. The conversation at Oxford is not merely about physical remnants but also about acknowledging the historical injustices faced by Indigenous communities due to colonial actions. The presence of these remains within the museum symbolizes a larger narrative of colonial exploitation and the ongoing struggle for indigenous rights and acknowledgment.

As conversations around the return of stolen Indigenous remains gain momentum globally, the situation in Nagaland reflects a growing awareness and demand for the restitution of looted cultural artifacts. Many communities around the world are increasingly vocal about claiming back their heritage. The calls for returning ancestral remains are part of a broader movement seeking justice for colonial legacies, highlighting the need to confront and rectify historical wrongs.

The discussions at the Pitt Rivers Museum have been a vital platform for the Naga tribes, offering an opportunity to articulate their perspectives on cultural survival and the significance of ancestral remains. These remains are not merely relics; they are imbued with cultural identity, history, and spiritual significance. For many Indigenous communities, the return of such artifacts is essential for healing and reconnecting with their heritage, which has been disrupted by colonial practices.

Moreover, the movement for the repatriation of artifacts and remains transcends specific cases, touching upon wider ethical considerations concerning museums and their roles in contemporary society. The dialogue emphasizes that institutions like the Pitt Rivers Museum have a moral responsibility to address the histories of the items in their collections and to reconsider practices that may perpetuate colonial narratives. There are growing expectations for museums to play a proactive role in fostering relationships with Indigenous communities and supporting their struggles for recognition and rights.

The conversations happening in Oxford echo a larger shift in societal attitudes toward art and cultural heritage. Increasingly, there is an understanding that museums, while they play important functions in education and preservation, must also engage in dialogue that supports truth-telling and reparations. This includes recognizing the rights of Indigenous communities to control narratives about their pasts and the artifacts associated with them.

Ultimately, the discussions surrounding the return of Naga ancestral remains at the Pitt Rivers Museum highlight a critical intersection of history, culture, and ethics. As more Indigenous groups articulate their demands for the return of cultural items and remains, institutions globally are challenged to respond in ways that honor these requests and acknowledge the complexities of historical relationships. This movement represents a profound step toward reestablishing dignity and respect for Indigenous identities and histories that have been marginalized for far too long.